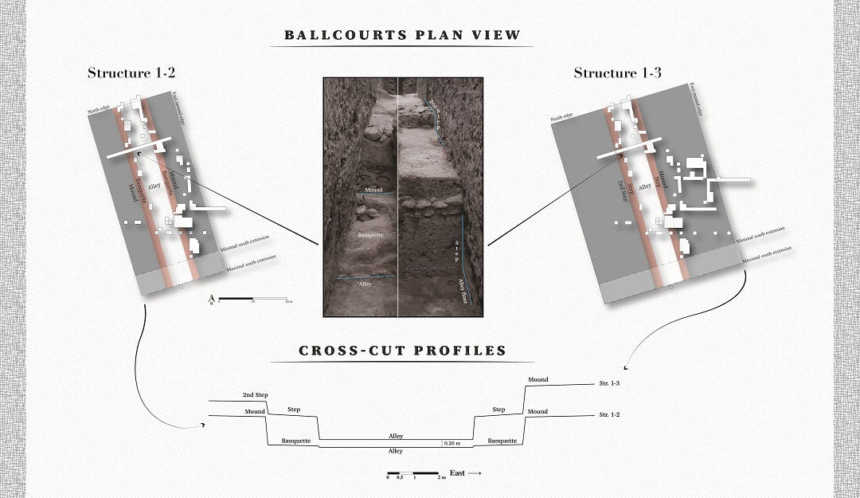

In 2015, archaeologists Jeffrey Blomster and Víctor Salazar Chávez began excavating the Mexican site of Etlatongo, a 3400-year-old village in the mountains of Oaxaca. They chose a spot in the center of the site, one that appeared to be an important public space. But instead of finding anything resembling a palace or a temple, the team unearthed a flat stone floor that extended at least 46 meters (about half the length of a soccer field), flanked by low steps made from clay and stone. Mounds at least 1 meter tall enclosed this narrow area on either side.

After several years of excavations and mapping, the scientists now conclude that the mysterious structure was a court used in a famous ballgame once played all over Mesoamerica. This court’s early date may point to the game’s important role in helping Mesoamerican societies develop social hierarchies and political complexity.

The court is dated at 3,400 years old — some 800 years older than any other ballcourt found thus far. The discovery suggests the game is far more ancient and far more popular across Mesoamerica than scientists realized.

Previously, researchers thought the game was played mainly in lowland areas of present-day Guatemala, Belize, Mexico, Honduras, and El Salvador. And it was perhaps as popular as modern-day soccer: 2,300 ballcourts have been discovered in these countries.

But it turns out people living in the region’s highlands — including Oaxaca — were playing the same game centuries before researchers had thought. This 3,400 year-old site offers the first evidence that both lowland and highland societies were part of the ballgame’s evolution.

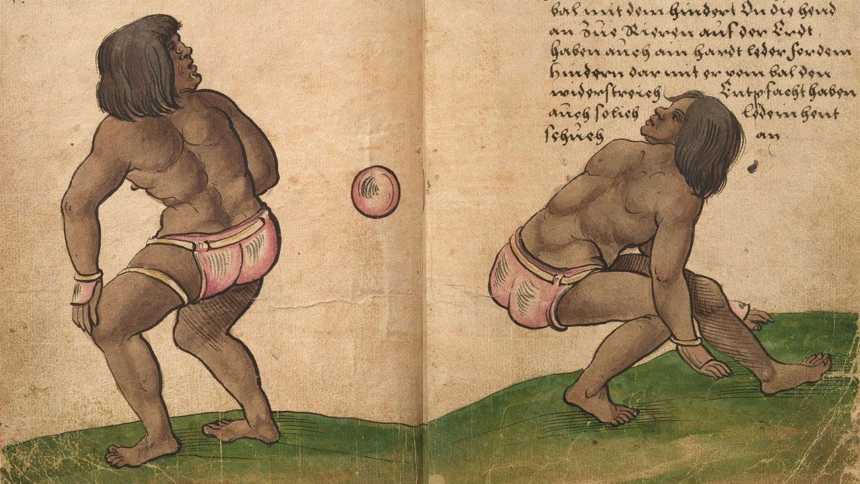

Although the exact game played at the time is unclear, many later versions resembled a combination of soccer and basketball that employed the hips: Players bounced rubber balls off their hips and through hoops mounted high on the court’s walls. The Etlatongo court doesn’t include hoops; at this early date, the game may have been more like hip-volleyball.

“We challenge the lowland paradigm by providing evidence that the earliest highland ballcourt dates to the Early Formative, nearly a millennium earlier than any previous highland architectural data,” the paper’s authors write. The researchers describe the site in a paper published Friday in the journal Science Advances.

The ball game wasn’t just for fun — it had religious and political uses as well.

The Etlatongo court existed during a transformative time in Mesoamerica, when the region’s first political and religious leaders emerged and trade between regions ramped up. “It’s the period when what we think of Mesoamerican culture begins,” Salazar Chávez says. The game would have helped strengthen alliances and trade between communities by bringing different teams together, and also given budding leaders a chance to flaunt their power and wealth by hosting feasts. The new phenomenon of inequality could have been reinforced by who was given the best positions on the courtside mounds to watch the game, Blomster says.

Shoring up the evidence for a ball court at Etlatongo are figurines found in the earth now on top of the ancient court. The human figures are wearing padded belts, a necessary piece of equipment for hitting heavy rubber balls with your hips. Similar figurines have been found at Mesoamerica’s first city, called San Lorenzo, which flourished on Mexico’s gulf coast between 1400 and 1000 B.C.E.

San Lorenzo was the first capital of the Olmec, the first culture in Mesoamerica to build large palaces and temples. In the past, many archaeologists thought the Olmec spread their religion and social structure through Mesoamerica, making it the region’s “mother culture.” But Etlatongo is 300 kilometers away from that coastal city, and even farther from Paso de la Amada. It’s also high in the mountains, unlike either of those sites.

The Etlatongo court’s surprising location “suggests that the ball game is an extremely old, broad tradition throughout Mesoamerica that doesn’t originate with any one group,” says David Anderson, an archaeologist at Radford University who has studied other ancient courts.

But Annick Daneels, an archaeologist at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico City, points out that the ball player figurines and much of the pottery found in Etlatongo were Olmec style, suggesting that the town’s court “could be inspired by Olmec contact.” Little of San Lorenzo has been excavated, she says, and an even earlier ball court could be waiting to be discovered there.

Archaeologists have found around 2,300 ball courts throughout Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica. Both the Maya and Aztec peoples played ball using rubber balls.

Since the rubber came from the Castilla elastica tree, which only grows on the lowland plains of southern Mesoamerica, researchers were surprised to find the ballpark at an elevation.

The oldest known ball court, Paso de la Amada, is located in the lowlands of Chiapas, Mexico, and dates to 1,650 BCE.