The Virupaksha Temple is one of the most stunning landmarks in India and the main center of pilgrimage at Hampi. Temple is noted for its architecture and has been listed among the UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Dating back 1,300 years, the magnificent structure consists of a layered tower of elaborate, hand-carved friezes populated by a bevy of Hindu deities and symbols.

Temple is also know as Pampapati Temple and it is constructed in Dravidian architecture style. It is located on the south bank of the river Tungabadra, in the ruins of the ancient city of Vijayanagar, capital of the Vijayanagara empire. The Virupaksha temple is dedicated to Lord Shiva, as the consort of the local goddess Pampa who is associated with the Tungabadra River. Virupaksha is an avatar of Lord Shiva, and among all the surrounding ruins, this temple is intact and is still in use.

It believed that this temple has been functioning uninterruptedly ever since its inception in the 7th century AD. That makes this one of the oldest functioning temples in India. This temple has ancient inscriptions which date back to 9th and 10th centuries.

Originally it was a small shrine, and the sanctuary of Virupaksha–Pampa (Shiva and Pampa) existed well before the foundation of the Vijayanagara Empire. However, the Vijayanagara rulers were responsible for building this small shrine into a large temple complex.

Evidence indicates there were additions made to the temple in the late Chalukyan and Hoysala periods, though most of the temple buildings are attributed to the Vijayanagar period. Over the centuries the temple gradually expanded into a sprawling complex with many sub shrines, pillared halls, flag posts, lamp posts, towered gateways and even a large temple kitchen.

The central pillared hall is the most ornate structure. Known as the Ranga Mandapa this pillared hall was added to the temple complex in 1510 AD by Krishadeva Raya.

In the 16th century, most of the wonderful decorative structures and creations were systematically destroyed by invaders. The cult of Virupaksha-Pampa did not die out after the destruction of the city in 1565. Worship there continued through the years, and at the beginning of the 19th century there were major renovations and additions, which included ceiling paintings and the towers of the north and east Gopur

Read More: Awe-Inspiring Ruins Of Hampi

Historian unlocks secrets of Virupaksha Temple at Hampi

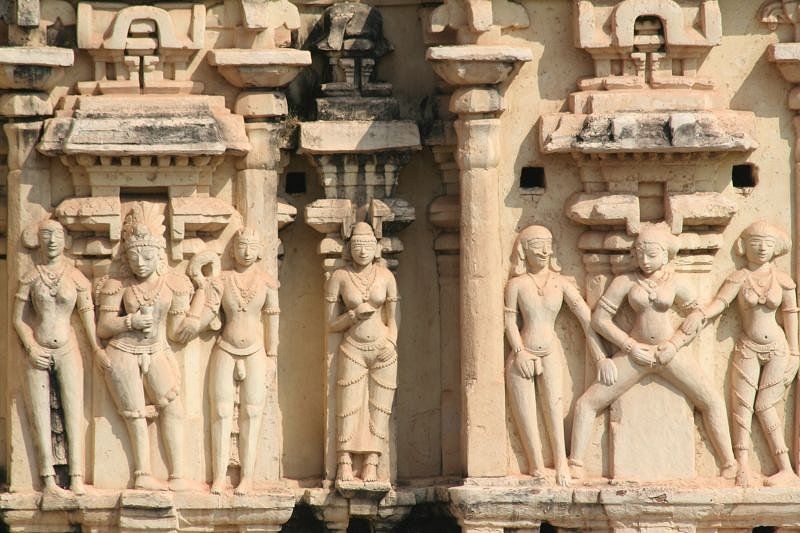

The temple is carved in stone, and its walls, pillars, panels and columns are decorated with beautiful carvings depicting episodes from Shiva’s life, different scenes from the Ramayana and the Mahabharata and scenes from Krishna’s childhood.

For a long time, there was an assumption that the sculptures on the outside of Hindu temples didn’t necessarily mean anything as a group. However, these figures are more than just architectural decoration, according to Cathleen Cummings, Ph.D., an associate professor in the UAB Department of Art and Art History, who devoted more than decades to study this art. According to Cummings, there were certain, very conscious choices being made as to where deities and specific forms of deities were placed.

Her discoveries identify images that glorify the king by referencing his family, conquests, and accomplishments, as well as other sculptural elements that offer religious guidance. Cummings describes one series of sequential inscriptions that depicts taking refuge in a deity, showing faith and then salvation. “It seemed like a clear sequence for devotees to follow,” she says. “It didn’t seem to be random images. There was a particular message that they could take away from it.”

Cummings’s research on the temple also sheds new light on the important role that women played in ancient Indian politics and culture. Queen Lokamahadevi, the chief wife of the king, Vikramaditya II, led the construction of the temple to the Hindu god Shiva during the early Chalukya dynasty, around the year 733. The queen wanted a temple “dedicated to the king’s reign and victory in wars with three other dynasties,” Cummings explains. Though women were part of the king’s inner circle, Cummings found the queen’s prominent placement in the temple’s iconography intriguing.

The builders didn’t leave many clues for Cummings to follow, however. “Apart from a few, very terse inscriptions on this and other Early Chalukya monuments, historians have not recovered much primary source documentation for this dynasty,” she says. Consequently, Cummings followed a scientific path, developing a hypothesis and following her instincts to find evidence to make her case. She pored over the placement of statues, studied Sanskrit inscriptions and ancient court documents from contemporary South Indian dynasties, investigated the temple’s rituals, and traveled to other Indian holy sites to build upon her findings. Teasing out the meanings behind the iconography was like an unfolding detective story, says Cummings, who is pleased that her work “fleshes out the Chalukya dynasty a lot more.”