Scientists believe that the race of dinosaurs was wiped out by an asteroid millions of years ago. Now, new research suggests that an early settlement of human also suffered the same fate around 12,800 years ago by a huge chunk of space rock. The event destroyed a village found in the Abu Hureyra dig site in Syria and splattered fragments of molten glass ‘hot enough to melt cars’ to the ground.

The site itself, an important one for documenting early agriculture in the region, is now underwater thanks to Lake Assad, but was “quickly excavated” between 1972 and 1973 before construction of the Tabqa Dam flooded the area, according to Smithsonian Magazine. Only later on did archaeologists realize they were really looking at two sites, with a Paleolithic hunter-gatherer settlement buried beneath a farming town made up of different style buildings.

A new analysis of samples of soil and artifacts salvaged from the original excavation has revealed a surprising finding: The Paleolithic village at Abu Hureyra was indirectly hit and destroyed by fragments of a comet that slammed into Earth about 12,800 years ago.

When the already-fractured comet entered Earth’s atmosphere some 13,000 years ago, researchers believe it broke off into several pieces, many of which never hit the ground, but instead, according to Smithsonian, “produced a string of explosions in the atmosphere known as airbursts. Each airburst was as powerful as a nuclear blast, instantaneously vaporizing the soil and vegetation underneath and producing powerful shock waves that destroyed everything for tens of kilometers around.”

The impact is also believed to have contributed to the extinction of many large animals, including mammoths as well as North American horses and camels. Experts believe the explosion helped bring about the demise of the North American Clovis culture and usher in an episode of climatic cooling.

Interestingly, the study’s lead author, Rochester Institute of Technology archaeologist and professor Andrew Moore, wasn’t thinking about comets when he first led the dig at Abu Hureyra back in the ‘70s. But he did notice “heavy burning” in one area of the village, which he now believes was the result of the airburst “incinerating the whole place.”

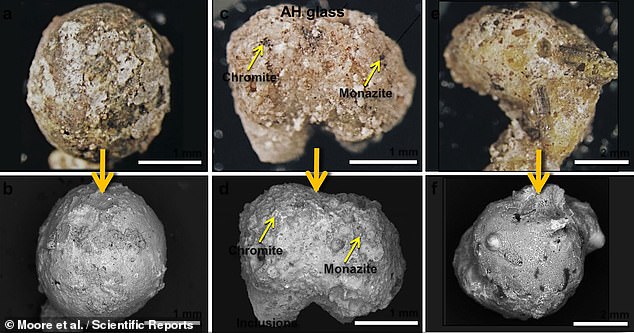

Supporting this theory, the multidisciplinary team discovered evidentiary shards of melt glass — or vaporized soil that quickly solidified — in soil samples, seeds, and cereal grains from the site. They also found melt glass attached to little pieces of bone, which tipped researchers off that the molten glass found living targets.

Further supporting the theory is the fact that the melt glass analyzed from the site contains “molten grains of minerals such as quartz, chromferide, and magnetite, which can melt only at temperatures ranging from 1,720°C to 2,200°C,” according to Smithsonian. That’s too hot for anything the locals could have mustered, and too hot even for natural sources such as fire or volcanism. And lightning was ruled out too, since the magnetic imprints you’d normally find weren’t present.

According to Professor Kennett, the air burst must have occurred close enough to the village to send heat and molten glass across the entirety of the settlement.

Experts had previously found evidence of meltglass deposits at another dig site — Pilauco, in southern Chile — however here only indirect evidence of human settlement, like the butchering of large animals, had been unearthed.

The full findings of the study were published in the journal Scientific Reports.