Depictions of humans hunting animals are common in the annals of Paleolithic cave art: In fact, we see prehistoric peoples brandishing spears and arrows at everything from rabbits to giant mammoths, presumably glorying in their predatory prowess. But depictions of the aftermath are anything but common. Now archaeologists report on the discovery of a grisly image in central India, depicting the disemboweling of a deer.

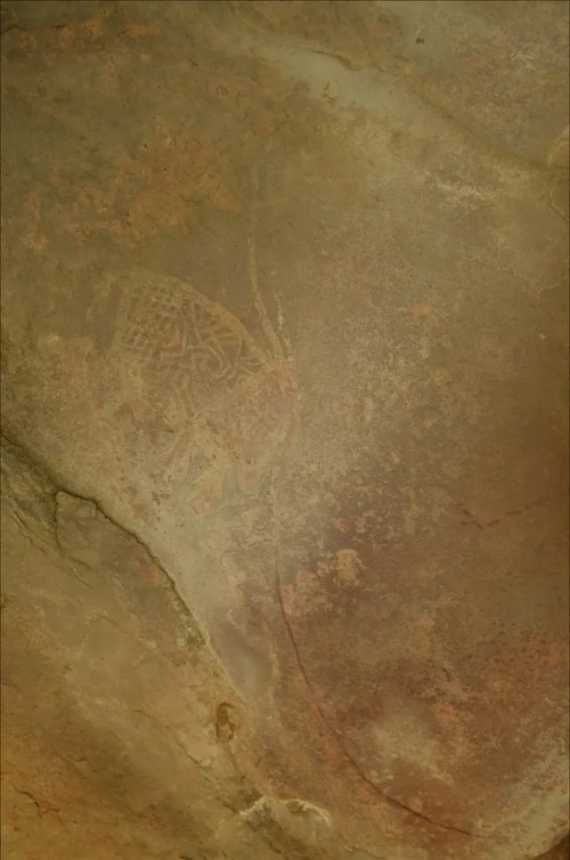

Found at rock shelter No. 6 at Maser, near the source of the Betwa River, the extraordinary image of the deer and its innards apparently dates to about 30,000 years ago, Shaik Saleem and Parth Chauhan of the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research, Mohali, report in the journal of Antiquity.

Stylistically but unarguably, it shows a man squatting by a dead deer, cutting into its belly. We can also clearly see an arrow sticking out of the deceased quadruped.

Cave art found in central India so far dates from about 30,000 years ago all the way to the Medieval period, 1,500 C.E., though Saleem explains that the dating of ancient works in the country remains qualified: “In India very few scientific efforts were put forward in order to establish absolute dates to different types of human as well as animal figures,” he explains to Haaretz. But a host of Paleolithic art, including the extraordinary Stone Age “collection” at the famed Bhimbetka site, in the foothills of the Vindhyan Mountains, are believed to have been made around 30,000 years ago. Bhimbetka has been named a UNESCO World Heritage site.

The depiction of the butchering of the deer, found by Saleem at Maser’s rock shelter number six – among 11 previously unknown sites he found by the river source – is only the second prehistoric image depiction of butchering in action found in India.

Very few depictions of post-hunt processing are known from elsewhere either. Prehistoric people seem to have been happy to boast of their hunting prowess but may not have associated manly valor to hacking up and roasting the corpse. And it isn’t that the residents of prehistoric Maser had some sort of predilection for depicting the result of the hunt. It’s the only butchery scene out of the 297 paintings found in nine newly discovered rock shelters in central India dating from prehistory to 600 C.E.

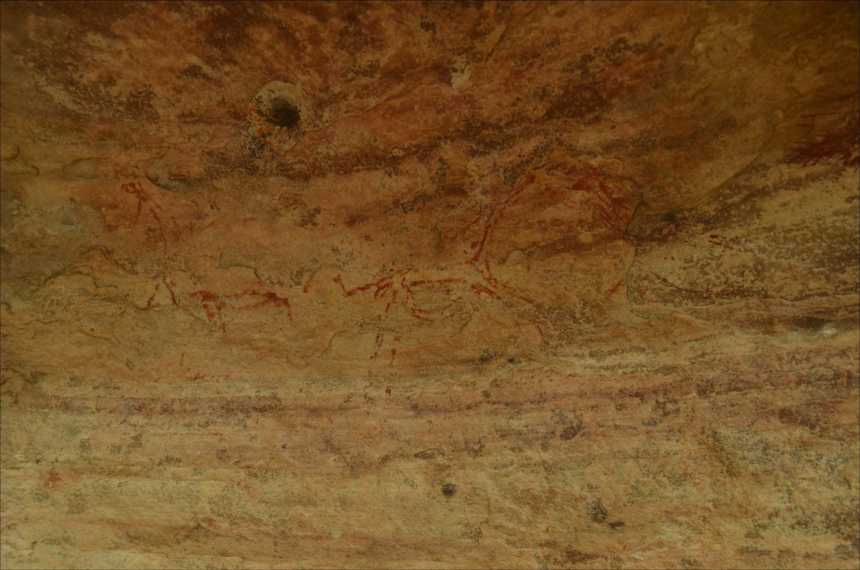

The other pictures at Maser show people and animals: mainly several species of deer, as well as a bison, a boar and a rhinoceros.

“A few stick-shaped human figures found at Maser were shown as hunting or dancing,” Shaik says, adding that “Similar stick-shaped human figures found at other rock art sites in Madhya Pradesh were shown as dancing, hunting, love-making and food collection scenes.”

Rock shelter No. 6, where the unfortunate ungulate and its innards were depicted, was the richest in art of the sites newly explored. It had 76 paintings, many of animals and people, as well as a flower and some sort of bird. “The bird figure found at Maser is similar to a crane or a saurus, but it is faded and difficult to identify,” Shaik says. There are other images too eroded to identify at all.

The deer with legs akimbo and stylized innards was painted together with one human figure bearing a bow and arrows walking toward it, and a second one, with an arrow in his left hand, squatting by the deer. A bow and spear lies by them on the ground. “Another partially visible arrow is depicted sticking out of the belly of the deer, suggesting that the deer had been hunted,” the authors write.

The human seems to be working on removing that arrow from the animal, which they postulate is a Barasingha swamp deer, which used to throng the whole region, but now only clings on in parts of India and Nepal.

Moreover, another human figure painted above these figures on the panel seems to be watching them. He and the postulated butcher are wearing feathered headdresses, Shauk and Chauhan write.

If their interpretation of the ancient faded drawings is accurate, the use of feathers is interesting in and of itself.

Why prehistoric peoples collected feathers and even the talons of magnificent birds – possibly even before the evolution of modern humans – must remain speculative, especially when discussing discoveries from as much as 420,000 years ago. A swan wing found at Qesem Cave in Israel from that time has cut marks that can only be from defeathering, ruled the researchers who found it.

The team analyzing the swan wing, Prof. Ran Barkai of Tel Aviv University and others, postulated based on that limb and a host of other evidence (such as non-utile tools made from elephant bones) that the prehistoric peoples would meticulously use all parts of animals they hunted, out of respect for them and their environment. Adornment with feathers and talons, in headdresses and pendants – as Neanderthals are postulated to have done, too – could attest to a belief system, possibly indicating identification with the animals, or the desire to “become” the animal to attain its strengths, to mark status – who knows. Any of these could apply to the utilization of feathers in prehistoric central India as well, or the reason could be otherwise.

Back in rock shelter No. 6 and the other cave sites in Maser, the animals were outlined realistically, and many such as the boar also featured geometric patterning not found in nature.

Despite the vast span of time, all the pictures were done in green, red and white, say the authors. Some rock sites have yellow, too, Shaik notes.

As said, in contrast to scenes of actual gory butchery, hunting scenes in cave art aren’t rare. Rock shelter No. 6 also has one. In it, eight stick figures armed with bows and arrows are chasing a deer. In fact, the earliest hunting scene found to date, a whole panel of paintings discovered in a cave in Indonesia and dating to around 44,000 years ago, seems to show bizarre hybrid human-animals (known as therianthropes) apparently aiming spears or ropes at pigs and bison.

As for the other prehistoric butchery scene in India, it was found at Chibbadnala, in the Chambal Valley.

Worldwide, few such are known, say the authors. One was found in a rock shelter in the Guadalupe Mountains of southern New Mexico, dating to about 6,400 to 3,520 years ago, and it also features people hunting with bows and arrows. That scene of butchery is even more gruesome than the newly discovered one in India. Painted in red, the deer is lying on its back – presumably dead – and seven humans are shown, two working in the large deer’s body cavity, others holding its legs apart and one holding its tail.

That Guadalupe rock shelter also has a picture of humans hunting rabbits, further demonstrating that prehistoric peoples did not eat only mega-fauna but anything they could catch. Early humans and Neanderthals and that sort hadn’t been expected to eat fleet-footed micro-mammals because catching them is a huge pain for very little meat, but it turns out they did. Also in New Mexico, one of many rock paintings found at White Oaks Spring may show a panel featuring deer hunting and butchering.

What could this rarity of butchering imagery, as opposed to the frequency of hunting images, suggest?

If anything, many of the depictions of the animals on Eurasian cave walls can be so sublime as to suggest the Stone Age artists and cultures not only hunted and ate but exalted the beasts. This rare picture of what happens next, after the hunt, doesn’t necessarily have to diminish from the theory of respect for animalia beyond the sheer utilitarian aspect of the predation, though one might wonder.

The truth is we can’t know thousands of years after the event what the artist had in mind, but perhaps it is legitimate to project from our own time.

So: Just think about how many people have posed for a photograph with some hapless beast they killed – not a mouse or cockroach ensnared in a glue-trap but a tiger or bear, or even some gentle giraffe that they shot, evidently feeling the depiction demonstrates some type of virility. Now think how many pictures show these hunters grubbing in the bowels of their target. The ancient artists of the Stone Age may have been exalting the beast, or themselves, or both, but at least a few also seem to have had a brutally practical side. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.