From 2600 to 1900 BC, the Indus Valley or Harappan Civilisation was at the zenith of its maturity as a sophisticated and technologically advanced urban cultural centre. In India, the most substantial and well-preserved remains of this Bronze Age urban culture can be witnessed at Rakhigarhi in Haryana, Kalibangan in Rajasthan, Rupar in Punjab and Dholavira and Lothal in Gujarat which happened to be the southern outpost of Harappan Civilisation. Among these, Lothal has been a significant port city for the trade of beads, gems and ornaments.

Situated in Bhal region of modern-day Gujarat, Lothal was excavated between 1955 and 1960 by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). The ASI museum at Lothal offers an insight into the town planning of this urban port. It exhibits some fine pieces of ceramics, metalwork and beads that were once created here. These included objects made from bronze, copper, stone, chert, shells and bones. It also showcases the uniformity of weights and measures used during the Harappan civilisation — bricks in perfect ratio while weights were based on units of 0.05, 0.1, 1.2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200 and 500, with each unit weighing around 28 g, similar to the English ounce or Greek uncia. Smaller objects were weighed in similar ratios with units of 0.871.

Lothal, according to ASI, had another series of weights that conformed to the Heavy Assyrian standards for international trade. The museum displays seals and toys reflecting trade with Persian Gulf and African ports. Principal exports were beads, ivory and shells. Key exhibits include a gold necklace, a copper figure, micro-beads, steatite and terracotta seals with motifs and inscriptions, metal fish hooks, ornaments like bangles, a perforated jar, a terra cotta bull, a horse, the model of a boat, objects used for games and a shell used as a compass for navigation. Two styles of pottery were also discovered at Lothal.

The development of Lothal as a trade centre probably stemmed from its sheltered harbour by Bhugavo River and Gulf of Khambatt, the suitability of the soil of the region called Bhal for growing grain and cotton and the already thriving bead-making industry in the Khambatt coastal region.

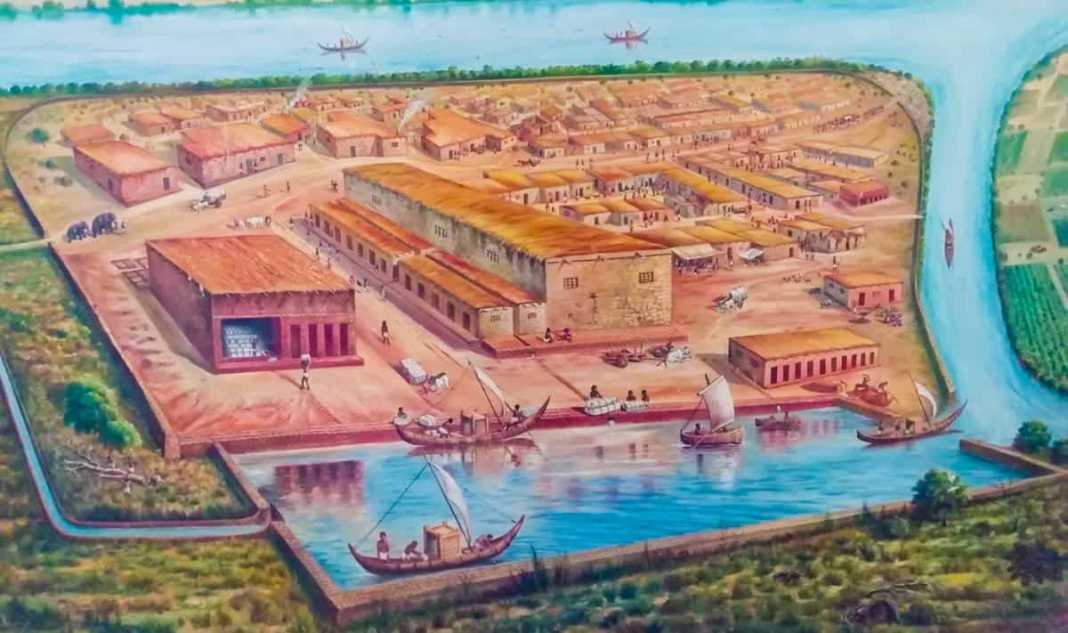

As one enters the excavated area, one can witness the tank which several archaeologists have opined as the world’s first dry dockyard. Plagued by floods in Sindh and realising the danger of high tides in the Gulf of Cambay, the Harappans are said to have built this dock inland, with a canal connecting to the estuary of River Sabarmati. The dock spans 37 m from east to west and 22 m from north to south. This showed a thorough study of tides, hydraulics and the effect of seawater on bricks.

According to an impression at the museum, ships could sluice into the northern end of the dock by an inlet channel connected to the estuary of River Sabarmati during high tide and the lock gates were closed so the water level would rise sufficiently for them to float. After the ships had loaded or unloaded cargo, the gates were opened for them to return to the sea. The tank’s dimensions indicate the dock could handle 60 ships of 30 tonnes each.

The warehouses near the dockyard were set on a 3.5 m high plinth. The cubical blocks used for warehousing were connected by passages built from kiln-fired bricks. Nearby is the acropolis where the powerful and wealthy inhabited since it featured paved baths, underground and surface drains and a drinking well. The foundations show a mansion that would have once existed on the acropolis. The proximity of the seat of power to the warehouse ensured a powerful person, perhaps a ruler, could inspect stocks easily from here.

The lower town contained commercial and residential areas. The arterial streets that led from north to south were probably flanked by shops, merchant dwelling and artisan’s workshops while the streets running from east to west led to the residential areas with lanes allowing access to individual dwellings. The bead factories comprised the main industry of the Harappans where agate and other semi-precious stones abound.

Drainage System

A unique aspect of planning was underground sanitary drainage. The main sewer, 1.5 m deep and 91 cm across, connected north-south and east-west ones and was constructed from smoothened bricks. These were joined together so expertly that not even a strand of hair could pass through the connections. Expert masonry kept the sewer watertight and drops at regular intervals acted as an automatic cleaning device. A wooden screen at the end of the drains held back solid wastes and liquid entered a cess pool made from radial bricks.