The Kingdom of Benin is home to one of the oldest civilization in Sub-Saharan Africa, It is home to the Edo people, a people of unparalleled creativity and ingenuity. It’s a place that has witnessed the birth of some of the greatest monarchs to ever walked the area called Nigeria.

The kingdom of Benin began in the 900s when the Edo people settled in the rainforests of West Africa. By the 1400s they had created a wealthy kingdom with a powerful ruler, known as the Oba. Gradually, the Obas won more land and built up an empire.

By 1300, Benin was heavily involved in trade and the arts, using such mediums as copper, bronze, and brass. The Benin bronzes eventually became some of the most famous art pieces produced in Africa.

When European merchant ships began to visit West Africa from the 15th century onwards, Benin came to control the trade between the inland peoples and the Europeans on the coast.

How did the kingdom begin?

Benin is believed to have been established before the eleventh century. It was founded by Edo-speaking peoples, but became more ethnically diverse when invaders from the grasslands of the Sudan settled and intermarried with local women. Based on oral tradition, Benin is said to have begun as family clusters of hunters, gatherers, and agriculturalists who eventually created villages.

Benin’s early society started as hierarchical, with an Ogiso (King of the Sky) as the head assisted by seven powerful nobles (uzama). These kings established the city on Ubini, later Benin City, in 1180 A.D.

Around 1300 the people of Benin rebelled against the Ogiso and invested power in a new ruler, Oranmiyan, who took over only long enough to have a child, Eweka I. Oranmiyan created a new dynasty, calling himself the first Oba (king) of Benin. The Obas would rule Benin for the next six centuries.

Around 1440, Ewuare became the new Oba of Benin. He built up an army and started winning land. He also rebuilt Benin City and the royal palace.

Oba Ewuare was the first of five great warrior kings. His son Oba Ozolua was believed to have won 200 battles. He was followed by Oba Esigie who expanded his kingdom eastwards to form an empire and won land from the Kingdom of Ife. Ozolua and Esigie both encouraged trade with the Portuguese. They used their wealth from trade to build up a vast army.

Oba Ehengbuda was the last of the warrior kings. But he spent most of his reign stopping rebellions led by local chiefs. After his death in 1601, Benin’s empire gradually shrank in size.

Trade with Europe

The fifteenth and sixteenth centuries marked the high-point of Benin’s economic and political power. The kings initiated military campaigns that extended the kingdom on all sides. They also began to trade with Europeans, especially the Portuguese who reached Benin City in 1485.

Benin exchanged palm oil, ivory, cloth, pepper, and slaves for metals, salt, cloth, guns, and powder. Although Benin’s earlier power rested with its domination of interior trade routes, commerce with the Europeans required expansion to the ocean since Benin City, the capital, was 50 miles inland. This problem, however, was solved with the creation of a fort and port on the coast.

Benin was desperate to keep trade with the Portuguese who supplied the guns that gave it military superiority over its neighbors especially after its attempt to manufacture guns locally failed. Recognizing his leverage, King Manuel I of Portugal threatened to end the gun trade unless Benin’s rulers adopted Christianity. The attempt failed but the Portuguese continued to supply guns because the slave trade proved too lucrative for either nation to end.

How did the kingdom end?

Benin began a slow decline in the 1700s as neighboring nations gained access to Portuguese or other European firearms. The kingdom was also weakened by internal disputes over royal succession which often led to civil wars. By the 1860s Benin was no longer a powerful empire and the Obas struggled to rule their people.

Benin was also under threat from Britain. The British wanted to gain control of Benin so they could get rich by selling its palm oil and rubber. By the 1890s, Benin was unable to resist British conquest. In 1897 it was incorporated into Great Britain’s Niger Coast Protectorate after a British force conquered and burned Benin City and in the process destroyed much of Benin’s treasured art while sending remaining pieces to London.

Benin Bronzes & Other Arts

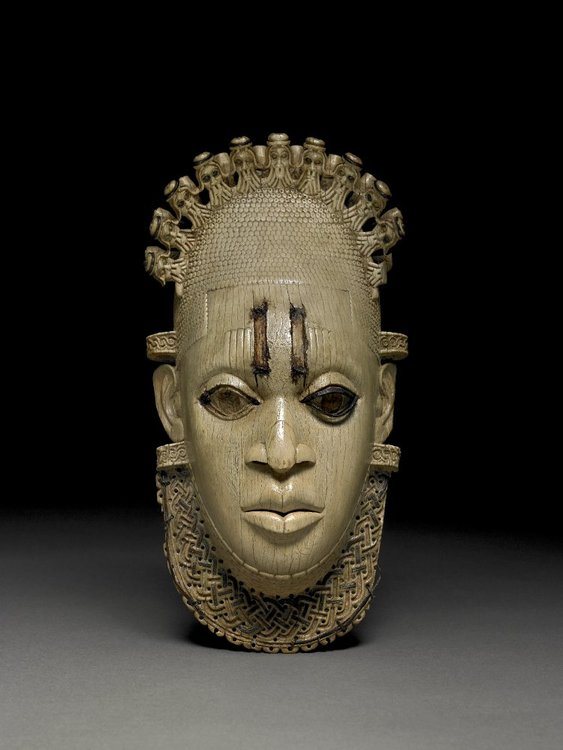

The Kingdom of Benin has produced some of the most renowned examples of African art. There are an estimated 2,400 to 4,000 known objects including 300 bronze heads, 130 elephant tusks, and 850 relief plaques. The art of the Kingdom of Benin, not to be confused with the Republic of Benin, is most widely known for its bronze plaques. Most of the ancient art of Benin is royal and honors the Oba, or king of the Benin Kingdom.

Whilst such metalwork has already been produced by the craftsmen of the Benin Empire as early as the 13th century, many of the Benin Bronzes were created between the 15th and 16th centuries.

The Benin Bronzes were seized by British forces during the Benin Expedition of 1897, and were given to the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. Many of the pieces were later sold, and ended up in the collections of museums around the world. Today, there are calls for the bronzes to be repatriated to their country of origin.

There are over nine hundred plaques of this type in various museums in England, Europe and America. Many of the plaques now in The British Museum were collected during the British Punitive Expedition in 1897. They are thought to have been made in matching pairs and fixed to pillars in the Oba’s palace in Benin City.